Insights

17 Feb, 2026

Five Products: When World’s Collide. The Changing Face of Cleaning

Read More

David Thomson & Toby Coates

07 Sep, 2022 | 6 minutes

In the world of consumer packaged goods, it’s an unfortunate but painful truth that most new products and almost all new brands fail to produce the projected financial returns. As a consequence, most are either delisted by key retailers or withdrawn by the manufacturer. Although some new products may be launched for what might be described as strategic reasons, the very high rate of new product failure is undeniably a long-standing problem in the packaged goods industry. More recently, increased sensitivity to the impact of business on the environment has added a new, ethical dimension to innovation that’s difficult to reconcile with the squandering of precious physical resources on new products that never really had a ghost of a chance of success. Now more than ever, consumer packaged goods companies need to address the inherent inefficiencies and wastefulness of their innovation processes. This is critical for the emerging consumer. Many young eyes are watching!

For a new product to be an economic success in-market, it must be adopted as a longer-term repertoire purchase by a large enough number of people, who are prepared to buy it frequently enough at a price that’s viable for both purchaser and seller. It really is that simple… and that difficult! Whilst stimulating new product trial and possibly even several rounds of repeat purchasing, is relatively easy, creating a new product that has the ‘intrinsic wherewithal’ to motivate and sustain longer-term adoption is much more challenging. Hence the high proportion of in-market failures!

First of all, why do consumer packaged goods manufacturers persist in launching new products against a backdrop of near-certain in-market failure? Perhaps it’s the possibility of that ‘big win’, just like punters playing the national lottery or more serious gamblers playing the slots! Perhaps it’s pressure from the ‘C-suite’ to innovate because that’s what forward-thinking companies (and executives) are supposed to do! Perhaps it’s just naivety or maybe it’s simply down to misplaced optimism: that most human but delusional trait that encourages us to believe that, somehow or other, we’ll defy the odds.

Secondly, why do modern innovation processes invariably yield new products that are destined to fail in-market? Innovation tends to create products that are optimized to deliver immediate pleasure rather than the wherewithal to motivate longer-term adoption. Although it may seem counterintuitive to some, the former alone will seldom deliver the latter.

Finally, why do the research tools used to evaluate new product viability predict (or otherwise fuel the delusion of) success, when in-market failure is the most likely outcome? Just as new product development defaults to creating products that deliver pleasure, most evaluative research methods default to predicting viability on the same, inappropriate basis.

This, in essence, is the innovation problem!

The fact that new product failure rates remain stubbornly high, in spite of the best efforts of developers, researchers and marketers alike, suggests that the solution to the innovation problem may lie, at least in part, beyond existing procedures. Having lost faith in traditional subjective (cognitive) research methodologies perhaps, and buoyed-up by suppliers’ exotic exhortations, some consumer goods companies are experimenting with objective (physical) research tools such as facial coding, galvanic skin response (GSR), electroencephalography (EEG) and brain imaging (fMRI), as a means of gauging consumers’ reactions to brand, product and packaging innovations. Unfortunately for them, these so-called ‘neuro methods’ are based on a what’s essentially a false premise. In all probability, there are no meaningful associations between any of these neurophysiological parameters and the complex mental activities that motivate purchasing behavior. This is what the science tells us! For more than 100 years, scientific study after scientific study has failed to establish any extent of neurophysiological specificity in the goal-oriented concepts and emotions that motivate our behavior. Inevitably, ‘neuro methods’ are already proving to be expensive, wasteful and insidiously misleading distractions.

Others have experimented with implicit methodologies. These are based on the entirely justifiable premise that we’re seldom aware of the full extent of mental activity that influences and otherwise motivates our behaviour. This has two important implications for product evaluation: Firstly, overarching quantitative assessments such as liking and purchase intent, may derive from an incomplete overview of all the many influences that motivate consumption behaviour. Secondly, and for broadly similar reasons, qualitative explanations offered by consumers may owe more to well-meaning but dubious post-rationalisations than to the elucidation of genuine behavioural influences. Implicit methods avoid direct questioning completely and rely on indirect measures such as reaction time, based on the premise that discordance causes hesitation. Laudable as this idea might be, when applied to the evaluation of new consumer packaged goods, the signal to noise ratio is typically very poor, making it difficult to interpret the data with any degree of confidence. Furthermore, implicit methods don’t provide diagnostic or remedial information and are difficult to design and implement in practice.

Whether or not the solution to the innovation problem lies in whole or in part with any of the emerging artificial intelligence-driven ‘tech’ research methodologies will depend, absolutely, on their capacity to access those influences that motivate and sustain longer-term product adoption. However, the fact that none of the research strategies described in the foregoing is capable of doing so, lies at the heart of the innovation problem.

Ironically perhaps, the answer probably doesn’t lie in the brave new world of artificial intelligence and machine learning but in the combination of two great but unrelated scientific discoveries that happened several generations ago.

Back in the early 1950s, in experiments involving electrical stimulation of a very specific part of the rat brain (incorrectly described as the ‘pleasure centre’), neuroscientists James Olds and Peter Milner found that the rats learned to depress a lever that would deliver a tiny electrical current to the so-called ‘pleasure centre’, and that they’d continue doing so repeatedly and often to the exclusion of almost everything else. It seemed that the rats were experiencing a form of immediate pleasure. This provided some degree of objective scientific confirmation to the previously unsubstantiated idea that animal behavior is motivated by reward, and that reward-motivated behavior can be learned.

Several decades later, another famous neuroscience duo, Morten Kringelbach and Kent Berridge, identified a different area of the brain, adjacent to but outside Olds and Milner’s ‘pleasure centre’, that was involved in what they described as ‘orchestrating cognitive aspects of meaningfulness [that are] important to happiness’. This seemed to provide physiological evidence in support of the long-standing notion of two aspects of reward which Plato had described over 2500 years ago (in ancient Greek) as hedonia (immediate pleasure) and eudaimonia (meaningfulness). Today, we call this the ‘Duality of Reward Hypothesis’, with the two aspects of reward variously described as reward delivered via immediate pleasure and reward via emotional outcomes. The former provides encouragement to do, (or not to do) things that are likely to be immediately beneficial (or harmful). The latter is a more sophisticated form of reward associated with those emotional outcomes that help us attain our personal ‘life goals’ (whatever these might be). Unsurprisingly, we tend to avoid emotional outcomes that impede the attainment of our personal goals.

Feeling love for another person or being loved by someone is an obvious example of this type of rewarding emotional outcome, where being wanted and cherished by others are goals that most people (but not everybody, alas) might wish to attain. On the other hand, the immediate attractiveness of a physically beautiful person and the pleasure associated with the human orgasm, are obvious examples of reward via immediate pleasure. The latter plays a role in initiating a relationship between couples whereas the former is crucial to maintaining it in the longer-term. The evolutionary importance of both to the furtherance of the human species is fairly obvious.

However, it’s not always that straightforward. Consider altruism; the seemingly selfless act of doing something that’s superficially costly to you but beneficial to others. In spite of the apparent cost, this may still be rewarding to you, as the benefactor, because being considered a ‘good person’ by others may be one of your personal goals. Alternatively, it could make you feel superior to the beneficiary of your patronage, and the desire to patronise and otherwise dominate others just happens to be one of your personal goals, even if you don’t realise it, or you don’t wish to admit it to yourself or anybody else. In reality, this seemingly selfless altruistic act is utterly selfish because you’re seeking reward via various emotional outcomes that help you attain your personal goals. Schadenfreude (deriving reward from the misfortunes of others) is another classic manifestation of reward via emotional outcomes. Why would the misfortunes of others be rewarding to you? Again, one of your personal goals might be to dominate others, or perhaps the downfall of others might help to assuage those nagging feelings of low self-worth that you harbour, knowingly or otherwise.

The foregoing examples illustrate the point that there’s another aspect of reward beyond immediate pleasure, that’s all about attaining your idiosyncratic and often hidden personal goals. This aspect of reward is hugely influential in motivating every aspect of your behavior including, we might reasonably assume, your personal consumption habits and the brands and products that you choose to include in your repertoire. It transpires that the product development procedures and the consumer research tools used to guide development and evaluate new products pre-launch, default to reward via immediate gratification and mostly fail to capture reward via emotional outcomes. The reason why this happens is readily explained by the second great scientific discovery alluded to earlier.

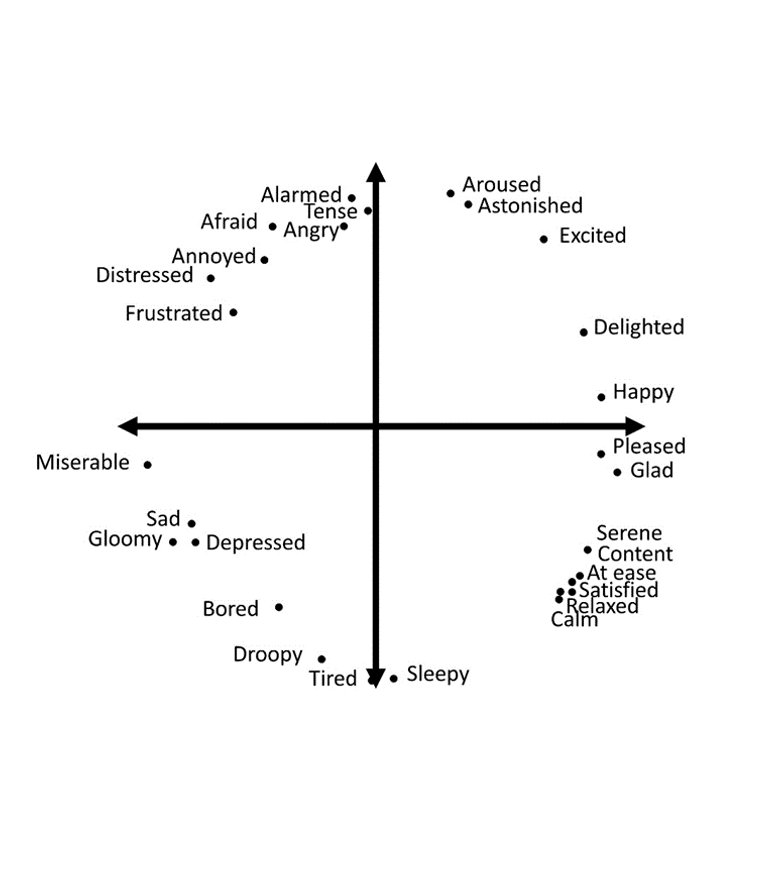

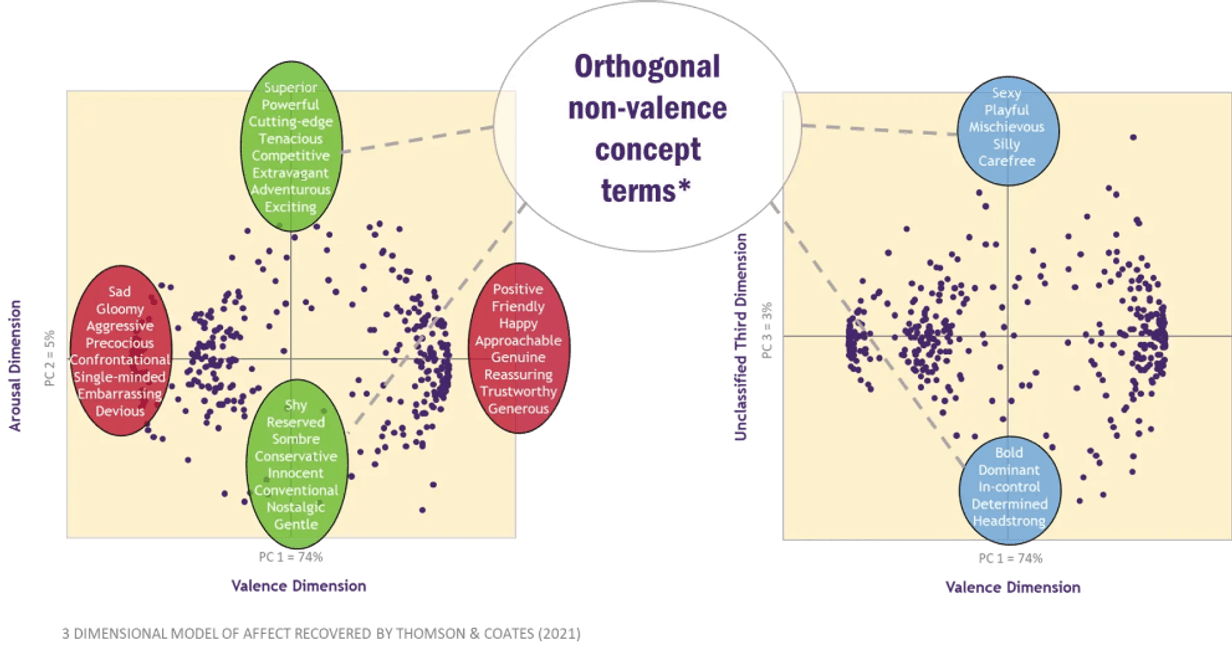

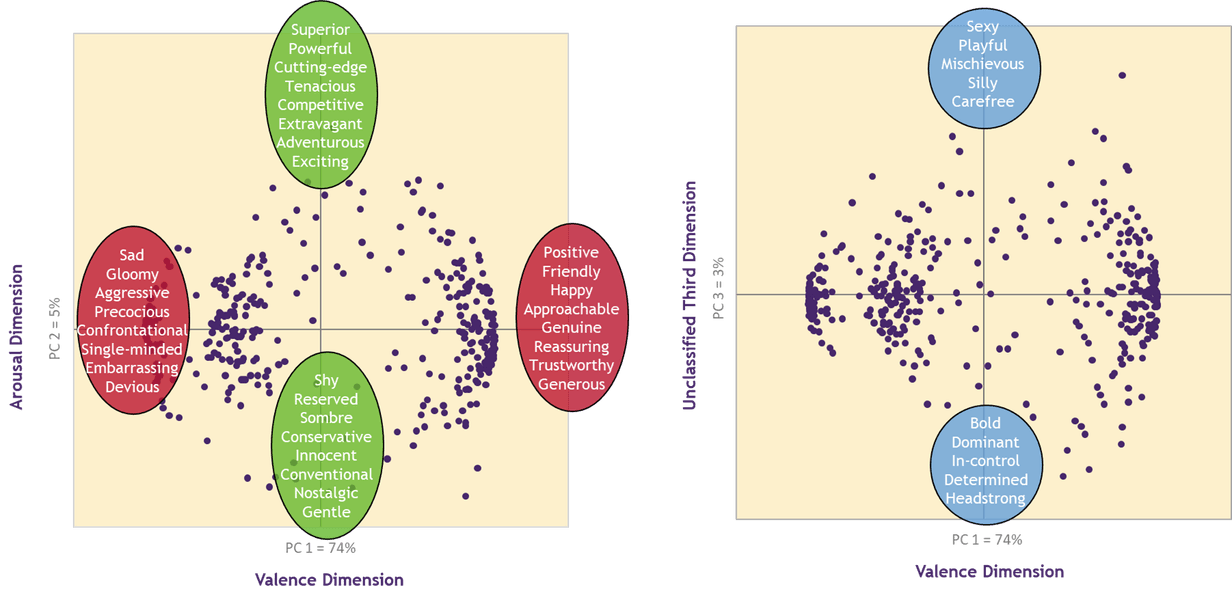

Whilst exploring conceptual associations amongst various words commonly used to describe emotions, American psychologist James Russell found that the emotion words mapped in a circle (subsequently known as the emotion circumplex). The dominant (horizontal) dimension was associated with pleasure (unpleasant – pleasant) which he described as valence. The second dimension he associated with arousal (inactive to active).

One of the most important features of this map is a property known as orthogonality. This means that the two dimensions of the map are at right angles to each other. Emotion words that map on the mid-point of the valence (pleasure) dimension but at either the top or bottom end of the arousal dimension are mathematically (and conceptually) unrelated to those emotion words that map at the midpoint of the arousal dimension but at either extremity of the valence dimension. We’ll come back to orthogonality in a moment because it really matters.

Many other researchers have replicated Russell’s work, some with relatively small numbers of emotion words, others (including ourselves at MMR) with many hundreds, and everything in between. Without exception, all of these studies identify pleasure as a super-dominant first dimension. Some studies have identified a third and even a fourth dimension in the ‘emotion space’, and when they do, Russell’s arousal dimension invariably emerges, although not always as the second dimension. However, the position of arousal in the dimensional hierarchy doesn’t really matter in the context of this discussion. What does matter is that it’s possible to harvest a relatively small number of emotion words from across the 2nd, 3rd and 4th dimensions of these various studies that are orthogonal to (i.e. not associated with) the pleasure dimension. On this basis, there are three categories of emotion words: Those associated solely with pleasure, those emotion words that map on the second, third, fourth, etc. dimensions that are orthogonal to the pleasure dimension (known as ‘orthogonal, non-valence emotion terms’) and those associated with pleasure and one or more of the other dimensions in the emotion space. It’s worth becoming familiar with the idea of orthogonal, non-valence emotion terms (and comfortable with the name) because these emotions, and the concepts upon which they are founded, are fundamental to the delivery of reward via emotional outcomes and consequently, to effective innovation.

There’s one last aspect of science to consider, in order to put the last piece of the jigsaw in place.

Earlier, it was mentioned that behavior is driven by reward and that the relationship between behavior and reward can be learned, often without the person concerned being aware of the fact. From this it follows that individuals’ routine consumption habits, and the brands and products that feature in their longer-term consumption repertoires (both of which are aspects of behavior) must, by definition, be sufficiently rewarding to allow them to maintain this status. Allied to this, it must also be recognized that different repertoire products will be included in a particular individual’s longer-term consumption repertoire for different reasons. For example, someone’s first choice of breakfast cereal will probably deliver reward differently from their first choice of chocolate bar.

Working on the premise that the repertoires of most individuals will already be saturated with products and that almost all (if not all) repertoire products will be there for good reason, this means that there are likely to be very few, if any, vacancies for new products. This, in turn means, that the challenge for any new product must be to squeeze in alongside, or squeeze out, products that are incumbents in the repertoires of individual consumers. In other words, somehow or other the new product must ‘out-reward’ individuals’ repertoire incumbents and it must continue to do so in the longer term. This is no mean feat!

Because it’s relatively easy to create new products that deliver high levels of immediate pleasure and because novelty is, in itself, a source of reward for some people, it’s easy to gain trial and possibly even several cycles of repeat purchasing, especially when consumers are induced to do so by engaging advertising and attractive pricing. However, as the superficial attractiveness of the new product wanes, novelty wears off and marketing budgets are exhausted, motivation to purchase typically declines and sales fizzle out. This is the eventual fate of most new products and of almost all new brands. In order to motivate purchase and consumption beyond this initial phase, any new product must be designed to deliver sufficiently high levels of reward via emotional outcomes, so as to challenge the products that are already incumbent in target individuals’ repertoires, and it must continue to do so over a relatively long period of time. This, in a nutshell, is the innovation challenge. Failure to recognize this, and failure to create new product development processes and research procedures that deliver new products to market that are able to compete on this basis, is the innovation problem.

With this in mind, the first step in any innovation programme must surely be to acquire a detailed understanding of the competitive landscape in which the prospective new product is likely to compete. This information should be gleaned from individual target consumers, one at a time, and not from consumers en masse, using old-school usage and attitude studies. By aggregating this information qualitatively rather than statistically, the product developer should begin to acquire an initial idea as to what the new product is likely to be used for (on a functional and psychological basis), when it would be used (not just the occasion but the mindset of the individual on such occasions), why it would be used and by whom (the ‘4 Ws’). The object of this first stage of the development programme is to identify (and retain for subsequent exploration) target consumers (i.e., who) and also to identify specific incumbent product(s) from within those individuals’ repertoires which the new product is likely to challenge (i.e., what) in specific consumption scenarios (i.e., when).

In the next stage of the development programme, the new product idea is set aside (temporarily) whilst researchers explore the targeted repertoire products of target consumers, to identify the emotional outcomes that motivate their purchase and consumption (i.e., why), using conceptual profiling. Consumers are generally unaware of the emotional outcomes that motivate their behaviour which means that any attempt to access this information via direct questioning is likely to encourage confabulation, if not fabrication.

Concept profiling works on the established principle that emotions arise as a reaction, at least in part, to the concepts which people associate with the objects around them (their repertoire products in this case). This, in turn, means that concept words (e.g. Product X is a ‘happy’ product) can be used as proxies for associated emotional outcomes (e.g. ‘happiness’). Again, this must be undertaken with individual target consumers (who), using established conceptual profiling procedures, followed by qualitative compilation and aggregation. The object is to identify the key concepts (why) that target consumers (who) associate with key usage scenarios (when).

The third stage of the development process is essentially creative, where the initial new product idea is modified and refined to integrate those key concepts identified in the previous stage and to remove any extraneous or redundant conceptual associations. The output from this stage should be one or possibly two single-minded and highly developed new product ideas presented as refined graphics.

In the fourth stage, the refined new product ideas are conceptually profiled using the retained target consumers and the profiles compared against their incumbent repertoire products. The object is to establish whether or not the new product idea can out-compete individuals’ repertoire incumbents in terms of these key concepts, thereby vesting in them, the power to displace. Without the power to displace, the new product idea is dead in the water and should either be refined (repeating the third and fourth stages) or abandoned.

The fifth stage is where power to displace is evaluated quantitatively. Two bespoke competitive sets are created for each target individual. The first set includes the individuals’ principal repertoire incumbent(s) and a small number of market competitors on the fringes of their repertoire and from outside their consideration set. A trade-off ‘chip game’ is then used determine which products are selected by the individual, as demonstrated via the allocation of the chips to specific products. A second set is created which is otherwise the same as the first but includes the new product idea. The object is to determine whether or not the presence of the new product diverts any of the chips away from the repertoire incumbent, in favour of the new product, thereby demonstrating power to displace. This is essentially proof of concept!

In the sixth and final stage, the new product idea is married with physical product and the whole, branded product is conceptually profiled to determine the impact of the product on the delivery of the key motivating concepts. At the very least, the physical product should not undermine key concept delivery. Ideally, it should enhance it!

This is where sensory optimization gets involved but crucially, sensory optimization to maximize Reward via Emotional Outcomes rather than Reward via Immediate Pleasure, and this is where the big difference lies! Traditional sensory optimization procedures that maximize consumers’ ratings on a liking scale (and hence mean liking ratings) largely default to optimizing Reward via Immediate Pleasure and may even have a deleterious effect on Reward via Emotional Outcomes. Conversely, sensory strategies that optimize Reward via Emotional Outcomes may have a deleterious effect on Reward via Immediate Pleasure and consequently, may depress mean liking ratings.

For the past 70 years or more, product developers have optimized products to maximize mean liking ratings in blind product tests. This strategy often works well enough in immature product categories. However, in mature product categories, where key competitors are likely to be highly refined, a significant improvement in mean liking ratings may have little or no impact on purchasing behavior and consequently, on sales. In spite of this, developers are often challenged to optimize the sensory characteristics of established products so that they achieve a significantly greater mean liking rating, or they outperform a competitor product, in the hope of stimulating additional sales. In new product development, the challenge is often to develop a product that matches or exceeds an arbitrary benchmark. Indeed, this ‘thinking’ is so embedded in product development mindsets that achieving these objectives may even become key performance indicators that determine career progression and annual bonuses. Consequently, to advocate a sensory optimization strategy that could potentially reduce a product’s mean liking rating, may seem counterintuitive, and will often be resisted vigorously. At the very least, it’s a ‘hard sell’. Unfortunately, this established mindset is one of the principal causes of in-market failure for new products and the associated waste of resources, so it’s time to think differently, if you dare!

Over the last three decades, MMR Research has acquired a formidable reputation for effective sensory optimization. As of 2022, MMR is the only research agency in the world that advocates, and has the knowhow and the experience to optimize Reward via Emotional Outcomes.

In finishing, there are two over-arching ideas that you need to take from all of this: Firstly, to succeed, a new product must change the behavior of individual consumers. Consequently, product developers need to understand what motivates the purchase and consumption choices of individuals within particular scenarios and then aggregate this information (either qualitatively or statistically) to identify commonalities. Secondly, for a new product to become a ‘game changer’, it has to be a ‘behavior changer’ for individual consumers. To be a ‘behavior changer’ it must have the wherewithal to displace incumbent products form individual consumer’s established repertoires. Without the power to displace, a new product has absolutely no chance of success. Most new products and almost all new brands don’t have the power to displace. You know the rest!